Formulation of an Environmental Ethic, Thirty Years On (Part Two)

Does my younger self's ethical approach hold water? The unconventional approach to environmental decision-making I envisioned as a student.

Do you like to geek out on philosophy? Are you interested in environmental points of view? Do you ever think about what you thought all those years ago?

If so, read on.

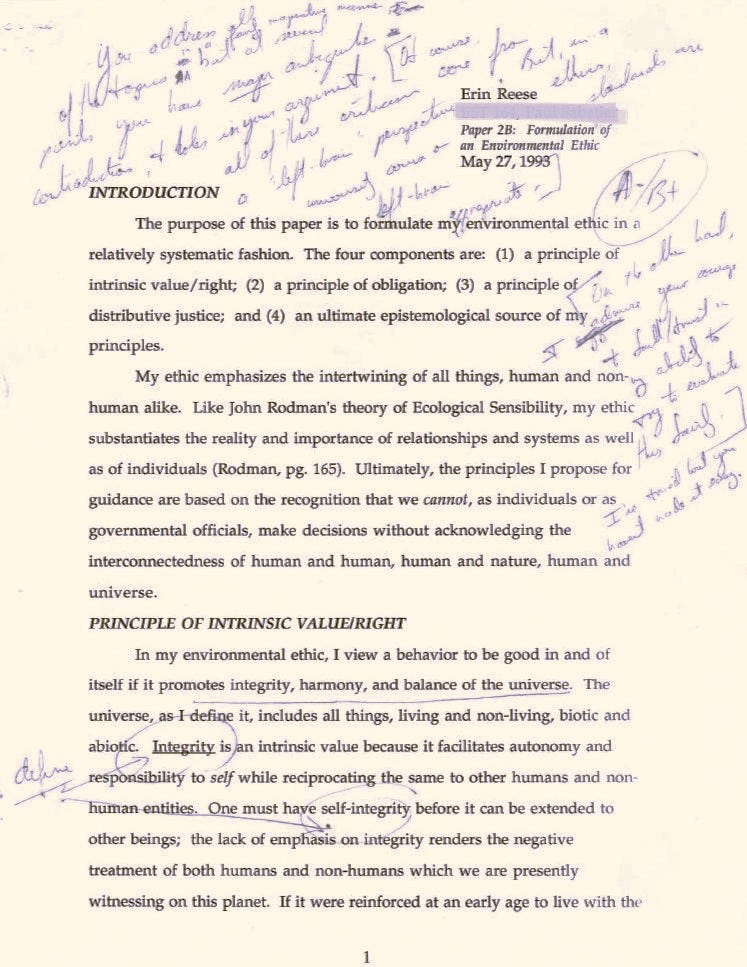

This piece follows Part One, audio and written versions of “Reflections on an Environmental Education, Thirty Years On.” The following paper, “Formulation of an Environmental Ethic” was written at the University of California, Davis in 1993. I share it here as an examination of change and stasis in ethics and perspective over time. It is also an example of an academic pummeling alongside a young person’s spiritual-intuitive emergence.

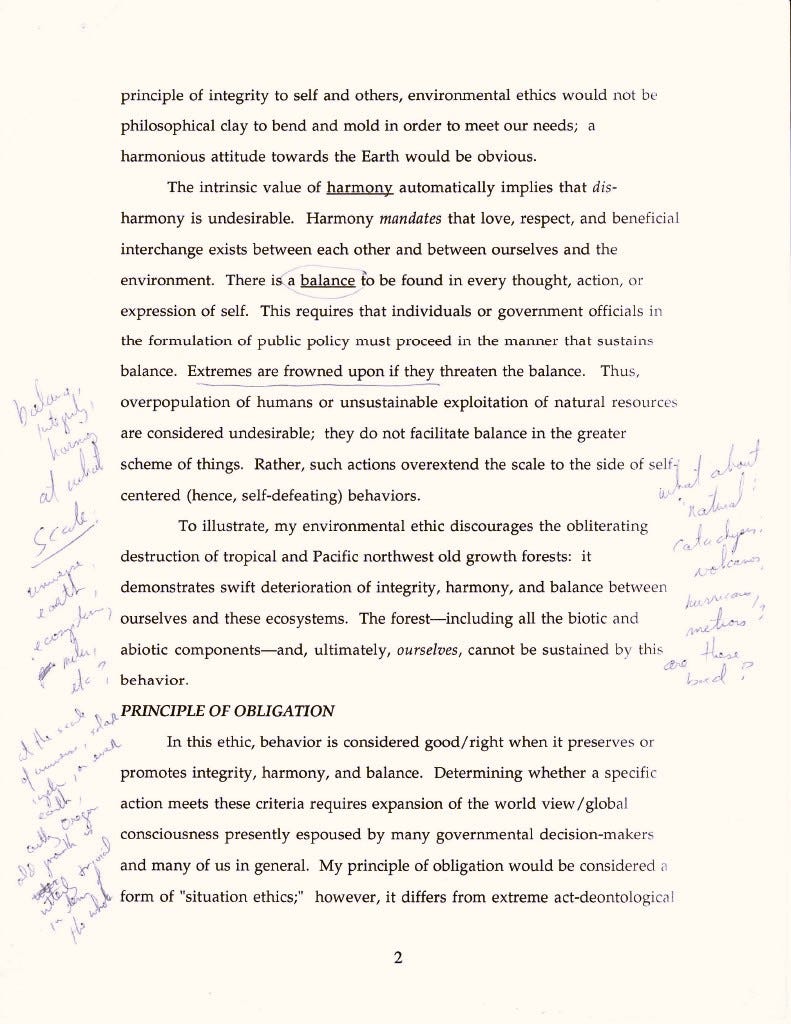

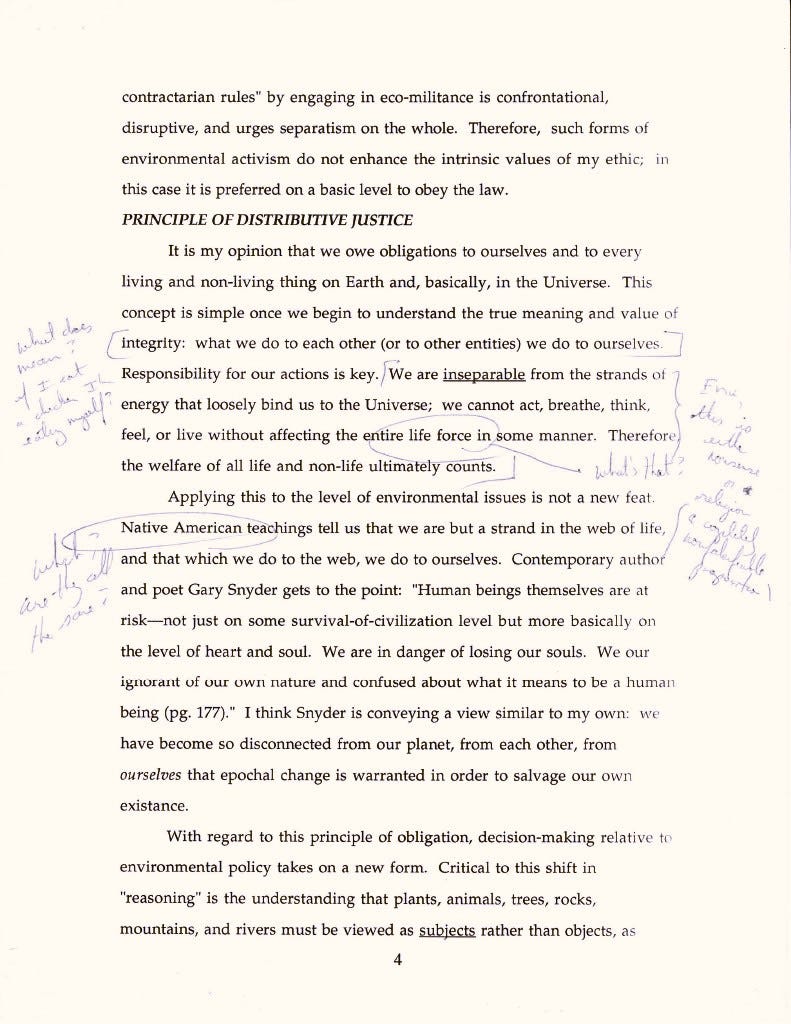

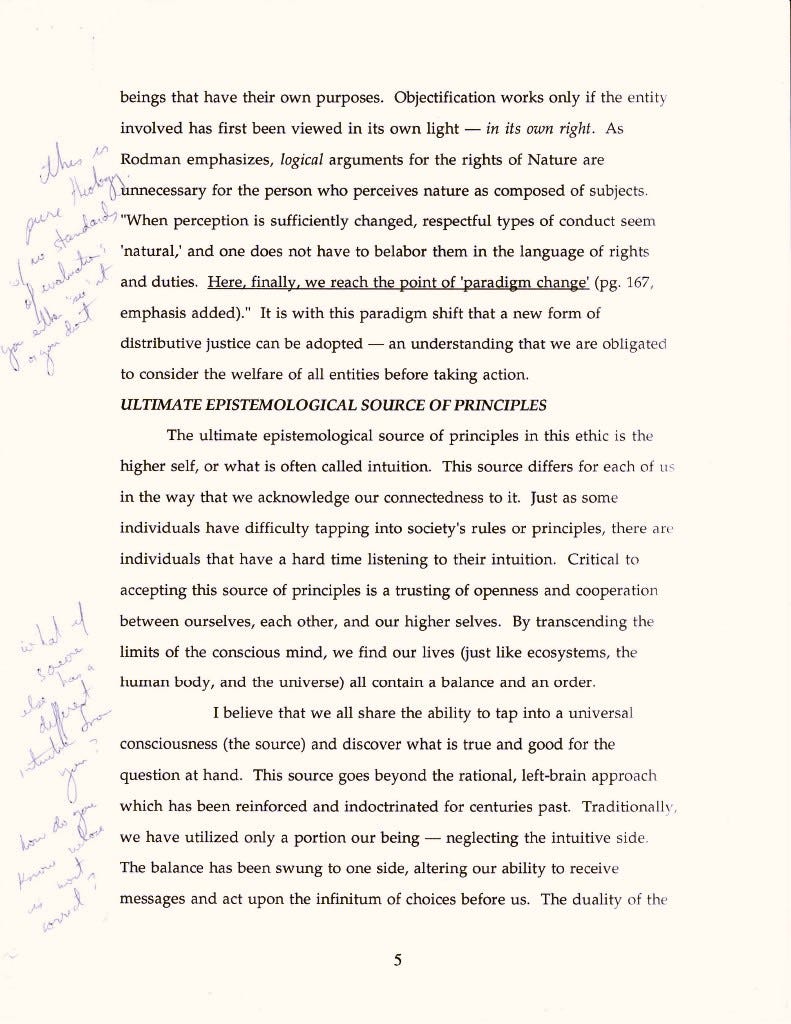

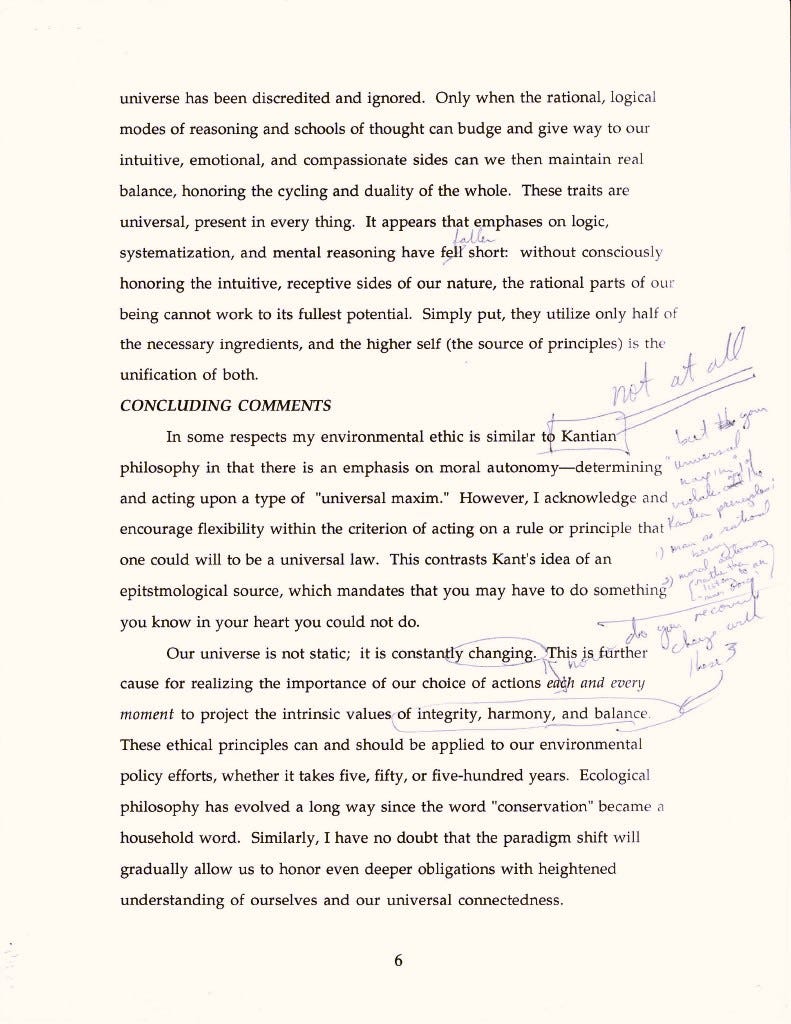

I’ve included footnotes at the end of each page; you'll see I’ve retyped several of the professor’s comments at the bottom of the post. Do check them out, for a combination of comedy and pathos. They are just as much a part of this “ethical confrontation” as the paper itself. I admire us both, for decently grappling with our respective points of view.

Your comments are welcome.

FOOTNOTES: Following are my professor’s scrawled comments, noted after each page above and retyped for ease of viewing.

“You address all of the topics in a fairly imaginative manner but at several points you have major ambiguities, contradictions, and holes in your argument. [Of course, all of these criticisms come from a “left-brain” perspective. But, in a university course on ethics, left-brain standards are appropriate.]

“On the other hand, I admire your courage and faith/trust in my ability to try to evaluate this fairly. I’ve tried but you haven’t made it easy.”

“Balance, integrity, harmony at what scale: universe, earth, ecosystem, meter, etc? At the scale of universe, solar system, or even earth, cutting Oregon old growth is utterly trivial in terms of the whole.”

“What about “natural” cataclysms: volcanoes, hurricanes, meteors? Are these bad?”

“Why then do most people not hear the same voice you do?”

“Erin, this is either nonsense or religion (a completely nonfalsifiable proposition).”

“This is pure theology with no standards of evaluation: you either ‘see’ it or you don’t.”

"What if someone else has a different intuition from you? How do you know whose is most correct?”

“But your ‘universal maxim’ violates most of the Kantian principles: (1) man as rational being; (2) moral autonomy (rather than listening to an ‘inner voice’).

Thanks for sharing this, Erin. I love your comment in the previous installment about being impressed with your previous self. I have had this feeling; sometimes I can hardly believe that I could have written that report or created that album, especially since it's been so long that it feels like I'm not the same person. This also reminds me that in 1989, in a course on SE Asian Economy during the MBA program at the University of Michigan, my final paper was on finding economic ways to stop the destruction of rain forests there. My classmates thought I was nuts...clearly one of those liberal arts types who'd somehow infiltrated the B-school. I wish I had that paper now :-)

Erin, thank you for sharing this. It was really eye-opening. First, I am amazed at how aware/awake you were. The eye-opening part was seeing how basic principles were seen as non-scientific, religious, etc. I thought of the book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance - how science can't grapple with the realm of quality. For me, your paper really showed up how science on its own is myopic. It felt troubling to see that not being understood - the problem not being seen. At the same time, it helped me make sense of the conflict science has with the subjective. I get why - religious history. But as you say in your paper, we need both.